History Behind The Day Celtic And Rangers Played As One In Early 9os

- The day Celtic and Rangers played as one – Old Firm, new friends.

On 12 April 1998, Alastair Campbell, the Downing Street press secretary, sat down to write a letter.

“An idea,” he started.

He went on to describe a vision which he hoped might cement support for the Good Friday Agreement, before the ground-breaking peace deal was put to a referendum in Northern Ireland.

It was certainly out of left field.

Campbell’s letter imagined a match between Celtic and Rangers – two teams divided by history, rivalry and religion – in Belfast.

“We could add to it by getting Celtic players to wear Rangers strips and Rangers players to wear Celtic strips”, he added, admitting that some players “may have difficulty with this”.

He sent the idea to Prime Minister Tony Blair, Northern Ireland Secretary of State Mo Mowlam and Scotland Secretary of State Donald Dewar.

None seemed enthused. There is no record of anyone responding.

Campbell has since admitted it was “perhaps not one of my better ideas”.

But, perhaps it wasn’t the worst either.

Because nearly 40 years before, the two Glasgow rivals had indeed come together in an extraordinary combined XI for a good cause.

The motivation wasn’t peace though. Instead, the hunt for the Loch Ness monster was behind the match.

In March 1933, Inverness Caledonian hosted the first football match in Scotland under modern floodlights, at their Telford Street Park ground.

“Inverness had given the lead to Scotland in regards to floodlit football,” reported The Press & Journal newspaper at the time.

The installation of lights brought Scottish football into a new, modern era and was revolutionary in 1933.

Floodlit football was rare – it had been tried numerous times in England, but it had been banned by the Football Association in August 1930 and would remain so, south of the border, until December 1950.

In Inverness, where the sun sets shortly after 16:00 GMT in the depths of winter, the floodlights were a great success. But they were short-lived too. They stayed in place for only a few weeks.

Because Caledonian had suddenly been supplanted as the biggest draw in town.

On 2 May 1933, the Inverness Courier published a story of a local businessman who was driving along the north shore of Loch Ness, when his wife let out a scream.

She had seen “a tremendous upheaval on the loch, which, previously, had been as calm as the proverbial mill-pond”.

The report continued describing an unknown creature, “rolling and plunging for fully a minute, its body resembling that of a whale, and the water cascading and churning like a simmering cauldron”.

And so the Loch Ness Monster phenomenon began.

Hundreds of people flocked to the Loch in the hope of glimpsing the monster. A circus impresario – Bertram Mills – put up a prize of £20,000 – equivalent of £1.24m today – for the person who caught it.

Mills added some stipulations to the competition – the creature had to be at least 20ft long, weigh more than 1,000lbs (454kg) and have previously been believed to be extinct.

No-one was put off by the small print. Crowds continued to grow on the shore and people camped out to try to spot the beast.

To assist with the search for Nessie, Caley’s pioneering football floodlights were dismantled and moved a few miles down the road to light up some of the 22 square miles of water.

No-one ever caught Nessie.

But more than 25 years later two brothers, William and Hugh MacDonald, paid for floodlighting to be installed for a second time at the Telford Street ground.

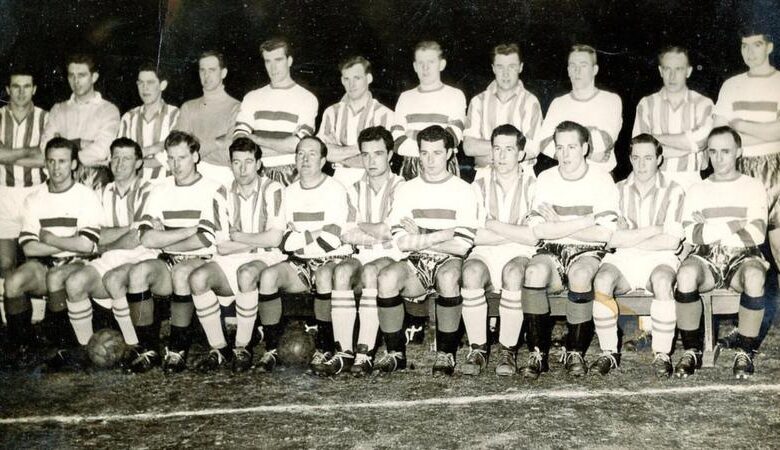

To celebrate the occasion, an Old Firm Select XI was invited up to Inverness to inaugurate the new set of lights.

It wasn’t totally without precedent. A Celtic and Rangers combined team had played in a testimonial match for Billy Meredith – one of football’s first stars – in 1925. But the concept had not been revived since and the rivalry between the two clubs seemed to make a repeat unlikely.

Celtic midfielder Paddy Crerand, raised in the Gorbals area of Glasgow by Irish immigrant parents, admitted being asked to play in the select team was “very strange” at first.

“Where I was from, Rangers weren’t a very popular club,” he told BBC Sport. “But we were all footballers and we were friendly with a lot of the Rangers players in those days anyway.

“There wasn’t the animosity amongst the Celtic and Rangers players that people may have thought.

“But I’m amazed Caledonian were able to organise a Celtic and Rangers select because the clubs were miles apart in those days.

“They couldn’t connect with each other unless they played with each other. It was a totally different world. There was so much anti-Catholicism about, it was ridiculous.”

But, somehow, the idea was approved. And Crerand was one of five Celtic players who would be included in the Celtic and Rangers combined XI.

Scottish League regulations at the time required all competing players to be signed to a single member club. The five Celtic players would have to sign for Rangers for the day on the trust that they would re-join Celtic the following day.

This would have been unheard of for supporters of both clubs.

A 19-year-old Jim Conway was one of the Celtic players who crossed the divide.

“For me, it was another football match and a great chance to play in this unique team,” he told BBC Sport. “Looking back, perhaps it was more of an important moment of unity.”

At the time, Rangers had an unwritten rule in place stating that as a club, they would not sign or employ a Roman Catholic.

When Mo Johnston signed for Rangers in 1989, some of the club’s fans laid a wreath outside Ibrox decrying the end of more than 100 years of history signalled by the signing of a Catholic.

But, albeit very briefly, Jim Conway, Paddy Crerand, Jim Kennedy and Charlie Tully had been part of breaking down that barrier 40 years before.

Conway recalls meeting up with the Rangers players at Glasgow Central station a few days before the game.

“Initially the Celtic and Rangers players were in two separate train carriages on the way up to the game,” Conway said.

“But then as time went on, I remember Dick Beattie who was the Celtic goalkeeper saying, ‘I’ve had enough of this’ and he got out a pack of cards and went to ask the Rangers players if they wanted to play.

“Soon, all of the players were all mixing and we were having a really good time and getting on well. Religion aside, family opinions aside, teams aside, supporters aside, we were just footballers doing our job.”

The select team was coached by the Rangers manager Scot Symon, described by Crerand as a ‘nice man’ and the team wore the Rangers’ away kit.

Conway remembers there being a big crowd in Inverness to watch the game.

“It was a huge moment and you can see why lots of people wanted to come out and watch us play,” Conway said.

Crerand said: “We were not used to playing under floodlights. It was a very new thing so it was great to do that. We got a great reception from the people. There wasn’t bigotry in Inverness those days, so they welcomed us.”

The match ended with Caley suffering a 4-2 defeat by the Old Firm select team.

Sammy Baird got a hat-trick and Conway scored the other goal for the visitors, while Rodwill Clyne and Jimmy Ingram replied for Caley.

“It was brilliant to score in that game. I felt really proud,” said Conway.

This game had longer-term effects for the players themselves.

“I got to know the Rangers players much better than I’d ever known them before because of that match,” Conway said.

“Certainly for me, it broke down barriers. I felt very comfortable speaking to the Rangers players and some, like Bobby King, became my great friends and subsequently our next-door neighbours when we both played together at Southend United, four years later.”

It was the last time, despite Campbell’s brief attempt, that Celtic and Rangers stars played in the same team.

But perhaps if it were a sight more regularly seen, then this game, like the Loch Ness monster, would lose its mystique and unique place in Scottish history.