History Of Football From Africa To The World

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal

football, also called association football or soccer, game in which two teams of 11 players, using any part of their bodies except their hands and arms, try to maneuver the ball into the opposing team’s goal. Only the goalkeeper is permitted to handle the ball and may do so only within the penalty area surrounding the goal. The team that scores more goals wins.

Football is the world’s most popular ball game in numbers of participants and spectators. Simple in its principal rules and essential equipment, the sport can be played almost anywhere, from official football playing fields (pitches) to gymnasiums, streets, school playgrounds, parks, or beaches.

Football’s governing body, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), estimated that at the turn of the 21st century there were approximately 250 million football players and over 1.3 billion people “interested” in football; in 2010 a combined television audience of more than 26 billion watched football’s premier tournament, the quadrennial month-long World Cup finals.

For a history of the origins of football sport, see football.

History

The early years

Modern football originated in Britain in the 19th century. Since before medieval times, “folk football” games had been played in towns and villages according to local customs and with a minimum of rules. Industrialization and urbanization, which reduced the amount of leisure time and space available to the working class, combined with a history of legal prohibitions against particularly violent and destructive forms of folk football to undermine the game’s status from the early 19th century onward.

However, football was taken up as a winter game between residence houses at public (independent) schools such as Winchester, Charterhouse, and Eton. Each school had its own rules; some allowed limited handling of the ball and others did not. The variance in rules made it difficult for public schoolboys entering university to continue playing except with former schoolmates.

As early as 1843 an attempt to standardize and codify the rules of play was made at the University of Cambridge, whose students joined most public schools in 1848 in adopting these “Cambridge rules,” which were further spread by Cambridge graduates who formed football clubs.

In 1863 a series of meetings involving clubs from metropolitan London and surrounding counties produced the printed rules of football, which prohibited the carrying of the ball. Thus, the “handling” game of rugby remained outside the newly formed Football Association (FA). Indeed, by 1870 all handling of the ball except by the goalkeeper was prohibited by the FA.

The new rules were not universally accepted in Britain, however; many clubs retained their own rules, especially in and around Sheffield. Although this northern English city was the home of the first provincial club to join the FA, in 1867 it also gave birth to the Sheffield Football Association, the forerunner of later county associations. Sheffield and London clubs played two matches against each other in 1866, and a year later a match pitting a club from Middlesex against one from Kent and Surrey was played under the revised rules.

In 1871 15 FA clubs accepted an invitation to enter a cup competition and to contribute to the purchase of a trophy. By 1877 the associations of Great Britain had agreed upon a uniform code, 43 clubs were in competition, and the London clubs’ initial dominance had diminished.

Professionalism

The development of modern football was closely tied to processes of industrialization and urbanization in Victorian Britain. Most of the new working-class inhabitants of Britain’s industrial towns and cities gradually lost their old bucolic pastimes, such as badger-baiting, and sought fresh forms of collective leisure. From the 1850s onward, industrial workers were increasingly likely to have Saturday afternoons off work, and so many turned to the new game of football to watch or to play.

Key urban institutions such as churches, trade unions, and schools organized working-class boys and men into recreational football teams. Rising adult literacy spurred press coverage of organized sports, while transport systems such as the railways or urban trams enabled players and spectators to travel to football games. Average attendance in England rose from 4,600 in 1888 to 7,900 in 1895, rising to 13,200 in 1905 and reaching 23,100 at the outbreak of World War I. Football’s popularity eroded public interest in other sports, notably cricket.

Leading clubs, notably those in Lancashire, started charging admission to spectators as early as the 1870s and so, despite the FA’s amateurism rule, were in a position to pay illicit wages to attract highly skilled working-class players, many of them hailing from Scotland. Working-class players and northern English clubs sought a professional system that would provide, in part, some financial reward to cover their “broken time” (time lost from their other work) and the risk of injury. The FA remained staunchly elitist in sustaining a policy of amateurism that protected upper and upper-middle class influence over the game.

The issue of professionalism reached a crisis in England in 1884, when the FA expelled two clubs for using professional players. However, the payment of players had become so commonplace by then that the FA had little option but to sanction the practice a year later, despite initial attempts to restrict professionalism to reimbursements for broken time.

The consequence was that northern clubs, with their large supporter bases and capacity to attract better players, came to prominence. As the influence of working-class players rose in football, the upper classes took refuge in other sports, notably cricket and rugby union. Professionalism also sparked further modernization of the game through the establishment of the Football League, which allowed the leading dozen teams from the North and Midlands to compete systematically against each other from 1888 onward.

A lower, second division was introduced in 1893, and the total number of teams increased to 28. The Irish and Scots formed leagues in 1890. The Southern League began in 1894 but was absorbed by the Football League in 1920. Yet football did not become a major profit-making business during this period. Professional clubs became limited liability companies primarily to secure land for gradual development of stadium facilities. Most clubs in England were owned and controlled by businessmen but shareholders received very low, if any, dividends; their main reward was an enhanced public status through running the local club.

Later national leagues overseas followed the British model, which included league championships, at least one annual cup competition, and a hierarchy of leagues that sent clubs finishing highest in the tables (standings) up to the next higher division (promotion) and clubs at the bottom down to the next lower division (relegation). A league was formed in the Netherlands in 1889, but professionalism arrived only in 1954. Germany completed its first national championship season in 1903, but the Bundesliga, a comprehensive and fully professional national league, did not evolve until 60 years later. In France, where the game was introduced in the 1870s, a professional league did not begin until 1932, shortly after professionalism had been adopted in the South American countries of Argentina and Brazil.

International organization

By the early 20th century, football had spread across Europe, but it was in need of international organization. A solution was found in 1904, when representatives from the football associations of Belgium, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland founded the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA).

Although Englishman Daniel Woolfall was elected FIFA president in 1906 and all of the home nations (England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales) were admitted as members by 1911, British football associations were disdainful of the new body. FIFA members accepted British control over the rules of football via the International Board, which had been established by the home nations in 1882.

Nevertheless, in 1920 the British associations resigned their FIFA memberships after failing to persuade other members that Germany, Austria, and Hungary should be expelled following World War I. The British associations rejoined FIFA in 1924 but soon after insisted upon a very rigid definition of amateurism, notably for Olympic football.

Other nations again failed to follow their lead, and the British resigned once more in 1928, remaining outside FIFA until 1946. When FIFA established the World Cup championship, British insouciance toward the international game continued. Without membership in FIFA, the British national teams were not invited to the first three competitions (1930, 1934, and 1938). For the next competition, held in 1950, FIFA ruled that the two best finishers in the British home nations tournament would qualify for World Cup play; England won, but Scotland (which finished second) chose not to compete for the World Cup.

Despite sometimes fractious international relations, football continued to rise in popularity. It made its official Olympic debut at the London Games in 1908, and it has since been played in each of the Summer Games (except for the 1932 Games in Los Angeles). FIFA also grew steadily—especially in the latter half of the 20th century, when it strengthened its standing as the game’s global authority and regulator of competition. Guinea became FIFA’s 100th member in 1961; at the turn of the 21st century, more than 200 nations were registered FIFA members, which is more than the number of countries that belong to the United Nations.

The World Cup finals remain football’s premier tournament, but other important tournaments have emerged under FIFA guidance. Two different tournaments for young players began in 1977 and 1985, and these became, respectively, the World Youth Championship (for those 20 years old and younger) and the Under-17 World Championship. Futsal, the world indoor five-a-side championship, started in 1989. Two years later the first Women’s World Cup was played in China. In 1992 FIFA opened the Olympic football tournament to players aged under 23 years, and four years later the first women’s Olympic football tournament was held. The World Club Championship debuted in Brazil in 2000. The Under-19 Women’s World Championship was inaugurated in 2002.

FIFA membership is open to all national associations. They must accept FIFA’s authority, observe the laws of football, and possess a suitable football infrastructure (i.e., facilities and internal organization). FIFA statutes require members to form continental confederations. The first of these, the Confederación Sudamericana de Fútbol (commonly known as CONMEBOL), was founded in South America in 1916. In 1954 the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) and the Asian Football Confederation (AFC) were established. Africa’s governing body, the Confédération Africaine de Football (CAF), was founded in 1957. The Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football (CONCACAF) followed four years later. The Oceania Football Confederation (OFC) appeared in 1966. These confederations may organize their own club, international, and youth tournaments, elect representatives to FIFA’s Executive Committee, and promote football in their specific continents as they see fit. In turn, all football players, agents, leagues, national associations, and confederations must recognize the authority of FIFA’s Arbitration Tribunal for Football, which effectively functions as football’s supreme court in serious disputes.

Until the early 1970s, control of FIFA (and thus of world football) was firmly in the hands of northern Europeans. Under the presidencies of the Englishmen Arthur Drewry (1955–61) and Stanley Rous (1961–74), FIFA adopted a rather conservative patrician relationship to the national and continental bodies. It survived on modest income from the World Cup finals, and relatively little was done to promote football in developing countries or to explore the game’s business potential within the West’s postwar economic boom. FIFA’s leadership was more concerned with matters of regulation, such as confirming amateur status for Olympic competition or banning those associated with illegal transfers of players with existing contracts. For example, Colombia (1951–54) and Australia (1960–63) were suspended temporarily from FIFA after permitting clubs to recruit players who had broken contracts elsewhere in the world.

Growing African and Asian membership within FIFA undermined European control. In 1974 Brazilian João Havelange was elected president, gaining large support from developing nations. Under Havelange, FIFA was transformed from an international gentlemen’s club into a global corporation: billion-dollar television deals and partnerships with major transnational corporations were established during the 1980s and ’90s. While some earnings were reinvested through FIFA development projects—primarily in Asia, Africa, and Central America—the biggest political reward for developing countries has been the expansion of the World Cup finals to include more countries from outside Europe and South America.

Greater professionalization of sports also forced FIFA to intercede in new areas as a governing body and competition regulator. The use of performance-enhancing drugs by teams and individual players had been suspected since at least the 1930s; FIFA introduced drug tests in 1966, and occasionally drug users were uncovered, such as Willie Johnston of Scotland at the 1978 World Cup finals. But FIFA regulations were tightened in the 1980s after the sharp rise in offenses among Olympic athletes, the appearance of new drugs such as the steroid nandrolone, and the use of drugs by stars such as Argentina’s Diego Maradona in 1994. While FIFA has authorized lengthy worldwide bans of players who fail drug tests, discrepancies remain between nations and confederations over the intensity of testing and the legal status of specific drugs.

As the sport moved into the 21st century, FIFA came under pressure to respond to some of the major consequences of globalization for international football. During the corrupt tenure of Switzerland’s Sepp Blatter as president from 1998 to 2015, the political bargaining and wrangling among world football’s officials gained greater media and public attention. Direct conflicts of interest among football’s various groups have also arisen: players, agents, television networks, competition sponsors, clubs, national bodies, continental associations, and FIFA all have divergent views regarding the staging of football tournaments and the distribution of football’s income. Regulation of player representatives and transfers is also problematic. In UEFA countries, players move freely when not under contract. On other continents, notably Africa and Central and South America, players tend to be tied into long-term contracts with clubs that can control their entire careers. FIFA now requires all agents to be licensed and to pass written examinations held by national associations, but there is little global consistency regarding the control of agent powers. In Europe, agents have played a key role in promoting wage inflation and higher player mobility. In Latin America, players are often partially “owned” by agents who may decide on whether transfers proceed. In parts of Africa, some European agents have been compared to slave traders in the way that they exercise authoritarian control over players and profit hugely from transfer fees to Western leagues with little thought for their clients’ well-being. In this way, the ever-widening inequalities between developed and developing nations are reflected in the uneven growth and variable regulations of world football.

Football Around The World

Regional Traditions

Europe

England and Scotland had the first leagues, but clubs sprang up in most European nations in the 1890s and 1900s, enabling these nations to found their own leagues. Many Scottish professional players migrated south to join English clubs, introducing English players and audiences to more-advanced ball-playing skills and to the benefits of teamwork and passing. Up to World War II, the British continued to influence football’s development through regular club tours overseas and the Continental coaching careers of former players. Itinerant Scots were particularly prominent in central Europe. The interwar Danubian school of football emerged from the coaching legacies and expertise of John Madden in Prague and Jimmy Hogan in Austria.

Before World War II, Italian, Austrian, Swiss, and Hungarian teams emerged as particularly strong challengers to the British. During the 1930s, Italian clubs and the Italian national team recruited high-calibre players from South America (mainly Argentina and Uruguay), often claiming that these rimpatriati were essentially Italian in nationality; the great Argentinians Raimondo Orsi and Enrique Guaita were particularly useful acquisitions. But only after World War II was the preeminence of the home nations (notably England) unquestionably usurped by overseas teams. In 1950 England lost to the United States at the World Cup finals in Brazil. Most devastating were later, crushing losses to Hungary: 6–3 in 1953 at London’s Wembley Stadium, then 7–1 in Budapest a year later. The “Magical Magyars” opened English eyes to the dynamic attacking and tactically advanced football played on the Continent and to the technical superiority of players such as Ferenc Puskás, József Bozsik, and Nándor Hidegkuti. During the 1950s and ’60s, Italian and Spanish clubs were the most active in the recruitment of top foreign players. For example, the Welshman John Charles, known as “the Gentle Giant,” remains a hero for supporters of the Juventus club of Turin, Italy, while the later success of Real Madrid was built largely on the play of Argentinian Alfredo Di Stefano and the Hungarian Puskás.

European football has also reflected the wider political, economic, and cultural changes of modern times. Heightened nationalism and xenophobia have pervaded matches, often as a harbinger of future hostilities. During the 1930s, international matches in Europe were often seen as national tests of physical and military capability. In contrast, football’s early post-World War II boom witnessed massive, well-behaved crowds that coincided with Europe’s shift from warfare to rebuilding projects and greater internationalism. More recently, racism became a more prominent feature of football, particularly during the 1970s and early 1980s: many coaches projected negative stereotypes onto Black players; supporters routinely abused nonwhites on and off the fields of play; and football authorities failed to counteract racist incidents at games. In general terms, racism at football reflected wider social problems across western Europe. In postcommunist eastern Europe, economic decline and rising nationalist sentiments have marked football culture too. The tensions that exploded in Yugoslavia’s civil war were foreshadowed during a match in May 1990 between the Serbian side Red Star Belgrade and the Croatian team Dynamo Zagreb when violence involving rival supporters and Serbian riot police spread to the pitch to include players and coaches.

Club football reflects the distinctive political and cultural complexities of European regions. In Britain, partisan football has been traditionally associated with the industrial working class, notably in cities such as Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester, and Newcastle. In Spain, clubs such as FC Barcelona and Athletic Bilbao are symbols of strong nationalist identity for Catalans and Basques, respectively. In France, many clubs have facilities that are open to the local community and reflect the nation’s corporatist politics in being jointly owned and administered by private investors and local governments. In Italy, clubs such as Fiorentina, Inter Milan, SSC Napoli, and AS Roma embody deep senses of civic and regional pride that predate Italian unification in the 19th century.

The dominant forces in European national football have been Germany, Italy, and, latterly, France; their national teams have won a total of seven World Cups and six European Championships. Success in club football has been built largely on recruitment of the world’s leading players, notably by Italian and Spanish sides. The European Cup competition for national league champions, first played in 1955, was initially dominated by Real Madrid; other regular winners have been AC Milan, Bayern Munich (Germany), Ajax of Amsterdam, and Liverpool FC (England). The UEFA Cup, first contested as the Fairs Cup in 1955–58, has had a wider pool of entrants and winners.

Since the late 1980s, topflight European football has generated increasing financial revenues from higher ticket prices, merchandise sales, sponsorship, advertising, and, in particular, television contracts. The top professionals and largest clubs have been the principal beneficiaries. UEFA has reinvented the European Cup as the Champions League, allowing the wealthiest clubs freer entry and more matches. In the early 1990s, Belgian player Jean-Marc Bosman sued the Belgian Football Association, challenging European football’s traditional rule that all transfers of players (including those without contracts) necessitate an agreement between the clubs in question, usually involving a transfer fee. Bosman had been prevented from joining a new club (US Dunkerque) by his old club (RC Liège). In 1995 the European courts upheld Bosman’s complaint, and at a stroke freed uncontracted European players to move between clubs without transfer fees. The bargaining power of players was strengthened greatly, enabling top stars to multiply their earnings with large salaries and signing bonuses. Warnings of the end of European football’s financial boom came when FIFA’s marketing agent, ISL, went bust in 2001; such major media investors in football as the Kirch Gruppe in Germany and ITV Digital in the United Kingdom collapsed a year later. Inevitably, the financial boom had exacerbated inequalities within the game, widening the gap between the top players, the largest clubs, and the wealthiest spectators and their counterparts in lower leagues and the developing world.

North and Central America and the Caribbean

Football was brought to North America in the 1860s, and by the mid-1880s informal matches had been contested by Canadian and American teams. It soon faced competition from other sports, including variant forms of football. In Canada, Scottish émigrés were particularly prominent in the game’s early development; however, Canadians subsequently turned to ice hockey as their national sport.

In the United States, gridiron football emerged early in the 20th century as the most popular sport. But, beyond elite universities and schools, soccer (as the sport is popularly called in the United States) was played widely in some cities with large immigrant populations such as Philadelphia, Chicago, Cleveland (Ohio), and St. Louis (Missouri), as well as New York City and Los Angeles after Hispanic migrations. The U.S. Soccer Federation formed in 1913, affiliated with FIFA, and sponsored competitions. Between the world wars, the United States attracted scores of European emigrants who played football for local teams sometimes sponsored by companies.

Football in Central America struggled to gain a significant foothold in competition against baseball. In Costa Rica, the football federation founded the national league championship in 1921, but subsequent development in the region was slower, with belated FIFA membership for countries such as El Salvador (1938), Nicaragua (1950), and Honduras (1951). In the Caribbean, football traditionally paled in popularity to cricket in former British colonies. In Jamaica, football was highly popular in urban townships, but it did not capture the imagination of the country until 1998, when the national team—featuring several players who had gained success in Britain and were dubbed the “Reggae Boyz”—qualified for the World Cup finals.

North American leagues and tournaments saw an infusion of professional players in 1967, beginning with the wholesale importation of foreign teams to represent American cities. The North American Soccer League (NASL) formed a year later and struggled until the New York Cosmos signed the Brazilian superstar Pelé in 1975. Other aging international stars soon followed, and crowds grew to European proportions, but a regular fan base remained elusive, and NASL folded in 1985. An indoor football tournament, founded in 1978, evolved into a league and flourished for a while but collapsed in 1992.

In North America football did establish itself as the relatively less-violent alternative to gridiron football and as a more socially inclusive sport for women. It is particularly popular among college and high school students across the United States. After hosting an entertaining World Cup finals in 1994, the United States possessed some 16 million football players nationwide, up to 40 percent of whom were female. In 1996 a new attempt at establishing a professional outdoor league was made. Major League Soccer (MLS) was more modest in ambition than NASL, being originally played in only 10 U.S. cities, with greater emphasis on local players and a relatively tight salary cap. The MLS proved to be the most successful American soccer league, expanding to 20 teams (with two in Canada) by 2016 while also signing a number of lucrative broadcasting deals with American television networks and some star players from European leagues. The United States hosted and won the Women’s World Cup finals in 1999, attracting enthusiastic local support. The success of the MLS and the Women’s World Cup led to the creation of a women’s professional league in 2001. The Women’s United Soccer Association (WUSA) began with eight teams and featured the world’s star player, Mia Hamm, but it disbanded in 2003.

North American national associations are members of the continental body, CONCACAF, and Mexico is the traditional regional powerhouse. Mexico has won the CONCACAF Gold Cup four times since it was first contested in 1991, and Mexican clubs have dominated the CONCACAF Champions Cup for clubs since it began in 1962. British influence in mining and railroads encouraged the founding of football clubs in Mexico in the late 19th century. A national league was established in 1903. Mexico is exceptional in that its mass preference for football runs counter to the sporting tastes of its North American neighbours. The national league system is the most commercially successful in the region and attracts players from all over the Western Hemisphere. Despite high summer humidity and stadiums at high elevations, Mexico has hosted two of the most memorable World Cup finals, in 1970 and 1986, from which Brazil and Argentina (led by the game’s then greatest players, Pelé and Maradona, respectively) emerged as the respective winners. While the national team has been ranked highly by FIFA, often figuring in the top ten, Mexico initially did not produce the world-class calibre of players expected of such a large football-crazed nation. Hugo Sanchez (at Real Madrid) was the only Mexican player to reach the highest world level in the 20th century, but the 21st saw a number of Mexican standouts excel with top European clubs.

South America

Football first came to South America in the 19th century through the port of Buenos Aires, Argentina, where European sailors played the game. Members of the British community there formed the first club, the Buenos Aires Football Club (FC), in 1867; about the same time, British railway workers started another club, in the town of Rosario, Argentina. The first Argentinian league championship was played in 1893, but most of the players belonged to the British community, a pattern that continued until the early 20th century.

Brazil is believed to be the second South American country where the game was established. Charles Miller, a leading player in England, came to Brazil in 1894 and introduced football in São Paulo; that city’s athletic club was the first to take up the sport. In Colombia, British engineers and workers building a railroad near Barranquilla first played football in 1903, and the Barranquilla FBC was founded in 1909. In Uruguay, British railway workers were the first to play, and in 1891 they founded the Central Uruguay Railway Cricket Club (now the famous Peñarol), which played both cricket and football. In Chile, British sailors initiated play in Valparaíso, establishing the Valparaíso FC in 1889. In Paraguay, Dutchman William Paats introduced the game at a school where he taught physical education, but the country’s first (and still leading) club, Olimpia, was formed by a local man who became enthusiastic after seeing the game in Buenos Aires in 1902. In Bolivia the first footballers were a Chilean and students who had studied in Europe, and in Peru they were expatriate Britons. In Venezuela, British miners are known to have played football in the 1880s.

Soon local people across South America began taking up and following the sport in ever greater numbers. Boys, mostly from poorer backgrounds, played from an early age, with passion, on vacant land and streets. Clubs and players gained popularity, and professionalism entered the sport in most countries around the 1930s—although many players had been paid secretly before then by their clubs. The exodus of South American players to European clubs that paid higher salaries began after the 1930 World Cup and has steadily increased.

By the late 1930s, football had become a crucial aspect of popular culture in many South American nations; ethnic and national identities were constructed and played out on an increasingly international stage. In South American nations, nonwhite players fought a successful struggle to play at the top level: in Rio de Janeiro, Vasco da Gama was the first club to recruit Black players and promptly stormed to the league championship in 1923, encouraging other clubs to follow suit. In Uruguay, a nation of largely mixed European descent, local players learned both the physical style played by the English and the more refined passing game of the Scots, producing a versatility that helped their national team win two Olympic championships and the World Cup between 1924 and 1930.

In 1916, South American countries were the first to hold a regular continental championship—later known as the Copa América. In 1960 the South American club championship (Libertadores Cup) was started; it has been played annually by the continent’s leading clubs (with the winner playing the European club champion), and, as a result of its popularity, various other international competitions have also been held between clubs. Domestic league championships are split into two or more tournaments each season with frequent variations in format.

Africa

European sailors, soldiers, traders, engineers, and missionaries brought football with them to Africa in the second half of the 19th century. The first documented match took place in Cape Town in 1862, after which the game spread rapidly throughout the continent, particularly in the British colonies and in societies with vibrant indigenous athletic traditions.

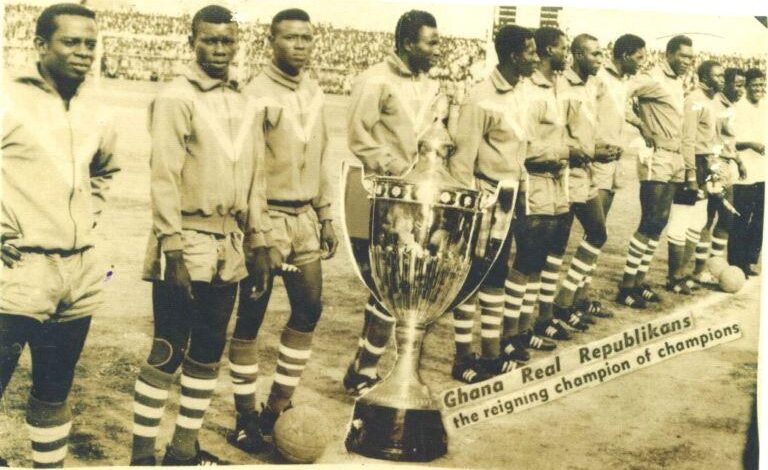

During the interwar period, African men in cities and towns, railroad workers, and students organized clubs, associations, and regional competitions. Teams from Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia competed in the North African championship, established in 1919, and vied for the North African Cup, introduced in 1930. South of the Sahara, Kenya and Uganda first played for the Gossage Trophy in 1924, and the Darugar Cup was established on the island of Zanzibar. In the mining centre of Élisabethville (now Lubumbashi, Congo) a football league for Africans was begun in 1925. In South Africa the game was very popular by the early 1930s, though it was organized in racially segregated national associations for whites, Africans, Coloureds (persons of mixed race), and Indians. In the colonies of British West Africa, the Gold Coast (now Ghana) launched its first football association in 1922, with Nigeria’s southern capital of Lagos following suit in 1931. Enterprising clubs and leagues developed across French West Africa in the 1930s, especially in Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire. Moroccan forward Larbi Ben Barek became the first African professional in Europe, playing for Olympique de Marseille and the French national team in 1938.

After World War II football in Africa experienced dramatic expansion. Modernizing colonial regimes provided new facilities and created attractive competitions, such as the French West Africa Cup in 1947. The migration of talented Africans to European clubs intensified. Together with his older compatriot Mario Coluña, Mozambican sensation Eusébio, European player of the year in 1965, starred for European champions Benfica of Lisbon and led Portugal to third place in the 1966 World Cup, where he was the tournament’s leading scorer. Algerian stars Rachid Mekhloufi of Saint-Étienne and Mustafa Zitouni of AS Monaco represented France before joining the team of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) in 1958. The FLN eleven, who lost only 4 of 58 matches during the period 1958–62, embodied the close relations between nationalist movements and football in Africa on the eve of decolonization.

With colonialism’s hold on Africa slipping away, the Confédération Africaine de Football (CAF) was established in February 1957 in Khartoum, Sudan, with the first African Cup of Nations tournament also played at that time. Independent African states encouraged football as a means of forging a national identity and generating international recognition.

In the 1960s and early ’70s, African football earned a reputation for a spectacular, attacking style of play. African and European coaches emphasized craft, creativity, and fitness within solid but flexible tactical schemes. Salif Keita (Mali), Laurent Pokou (Côte d’Ivoire), and François M’Pelé (Congo [Brazzaville]) personified the dynamic qualities of football in postcolonial Africa.

In the late 1970s, the migration of talented players overseas began hampering domestic leagues. The effects of this player exodus were somewhat tempered by the rise of “scientific football” and defensive, risk-averting tactics, an international trend that saw African players fall out of favour with European clubs. Even so, the integration of Africa and Africans into world football accelerated in the 1980s and ’90s. Cameroon’s national team, known as the Indomitable Lions, was a driving force in this process. After being eliminated without losing a match at the 1982 World Cup in Spain (tied with Italy in its group, Cameroon lost the tiebreaker on the basis of total goals scored), Cameroon reached the quarterfinals at the 1990 World Cup in Italy, thereby catapulting African football into the global spotlight. Nigeria then captured the Olympic gold medal in men’s football at the Summer Games in Atlanta in 1996; in 2000 Cameroon won its first Olympic gold medal in men’s football at the Games in Sydney, Australia. Success also came at youth level as Nigeria (1985) and Ghana (1991 and 1995) claimed under-17 world titles. Moreover, Liberian striker George Weah of Paris St. Germain received the prestigious FIFA World Player of the Year award in 1995.

In recognition of African football’s success and influence, FIFA awarded Africa five places in the 32-team 1998 World Cup finals. This achievement bears witness to African football’s phenomenal passion, growth, and development. This rich and complex history is made more remarkable by the continent’s struggles to cope with a fragile environment, scarce material resources, political conflicts, and the unpleasant legacy of imperialism.

Asia and Oceania

Football quickly entered Asia and Oceania in the latter half of the 19th century, but, unlike in Europe, it failed to become a unifying national sport. In Australia it could not dislodge the winter games of Australian rules football (codified before soccer) and rugby. British immigrants to Australia did relatively little to develop football locally. Because southern European immigrants were more committed to founding clubs and tournaments, football became defined as an “ethnic game.” As a result, teams from Melbourne and Sydney with distinctive Mediterranean connections were the most prominent members of the National Soccer League (NSL) when it started in 1977. The league has widened its scope, however, to include a highly successful Perth side, plus a Brisbane club and even one from Auckland, New Zealand. The NSL collapsed in 2004, but a new league, known as the A-League, emerged the next year.

In New Zealand, Scottish players established clubs and tournaments from the 1880s, but rugby became the national passion. In Asia, during the same germinal period, British traders, engineers, and teachers set up football clubs in such colonial outposts as Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Burma (Myanmar). Yet football’s major problem across Asia, until the 1980s, was its failure to establish substantial roots among indigenous peoples beyond college students returning from Europe. Football in India was particularly prominent in Calcutta (Kolkata) among British soldiers, but locals soon adopted cricket. In Japan, Yokohama and Kobe housed large numbers of football-playing foreigners, but local people retained preferences for the traditional sport of sumo wrestling and the imported game of baseball.

At the turn of the 21st century, football became increasingly important in Asian societies. In Iran, national team football matches became opportunities for many to express their reformist political views as well as for broad public celebration. The Iraqi men’s team’s fourth-place finish at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens struck a chord of hope for their war-torn homeland.

The Asian game is organized by the Asian Football Confederation, comprising 46 members in 2011 and stretching geographically from Lebanon in the Middle East to Guam in the western Pacific Ocean. The Asian Cup for national teams has been held quadrennially since 1956; Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Japan have dominated, with South Korea a regular runner-up. These countries have also produced the most frequent winners of the annual Asian Club Championship, first contested in 1967.

Asian economic growth during the 1980s and early 1990s and greater cultural ties to the West helped cultivate club football. Japan’s J-League was launched in 1993, attracting strong public interest and a sprinkling of famous foreign players and coaches (notably from South America). Attendance and revenue declined from 1995, but the league survived and was reorganized into two divisions of 16 and 10 clubs, respectively, by 1999. The league grew to 30 teams by 2005 but had reduced to 18 by 2018.

Some memorable international moments have indicated the potential of football in Asia and Oceania. Asia’s first notable success was North Korea’s stunning defeat of Italy at the 1966 World Cup finals. In 1994 Saudi Arabia became the first Asian team to qualify for the World Cup’s second round. The entertaining 2002 World Cup hosted by Japan and South Korea and the on-field success of the host nations’ national teams (South Korea reached the semifinals; Japan reached the second round) stood as the region’s brightest accomplishment in international football.

Football’s future in Asia and Oceania depends largely upon regular competition with top international teams and players. Increased representation in the World Cup finals (since 1998 Asia has sent four teams, and since 2006 Oceania has had a single automatic berth) has helped development of the sport in the region. Meanwhile, domestic club competitions across Asia and Oceania have been weakened by the need for top national players to join better clubs in Europe or South America to test and improve their talents at a markedly higher level. One promising development for the continent came in 2010 when Qatar was announced as the host of the 2022 World Cup, which will be the first World Cup held in the Middle East.

Spectator problems

The spread of football throughout the globe has brought together people from diverse cultures in celebration of a shared passion for the game, but it has also spawned a worldwide epidemic of spectator hooliganism. High emotions that sometimes escalate into violence, both on and off the field, have always been a part of the game, but concern with fan violence and hooliganism has intensified since the 1960s. The early focus of this concern was British fans, but the development of the anti-hooligan architecture of football grounds around the world points to the international scope of the problem. Stadiums in Latin America are constructed with moats and high fences. Many grounds in Europe now ban alcohol and no longer offer sections where fans can stand; those “terraces,” which charged lower admission than ticketed seating, were the traditional flash points of fan violence.

Some of the first modern hooligan groups were found in Scotland, where religious sectarianism arose among the supporters of two Glasgow teams: Rangers, whose fans were predominantly Protestant unionists, and Celtic, whose fans were drawn largely from the city’s sizeable Irish Catholic community. Between the World Wars, “razor gangs” fought street battles when these two clubs met. Since the late 1960s, however, English fan hooliganism has been even more notorious, especially when English supporters have followed their teams overseas. The nadir of fan violence came during the mid-1980s. At the European Cup final in 1985 between Liverpool and the Italian club Juventus at Heysel Stadium in Brussels, 39 fans (38 Italian, 1 Belgian) died and more than 400 were injured when, as Liverpool supporters charged opposing fans, a stadium wall collapsed under the pressure of those fleeing. In response, English clubs were banned from European competition until 1990, but by then hooliganism had become established in many other European countries. By the turn of the 21st century, self-identifying hooligans could be found among German, Dutch, Belgian, and Scottish supporters. Elsewhere, militant fans included the ultras in Italy and southern France, and the various hinchadas of Spain and Latin America, whose levels of violence varied from club to club. Argentina has experienced perhaps the worst consequences, with an estimated 148 deaths between 1939 and 2003 from violent incidents that often involved security forces.

The causes of football hooliganism are numerous and vary according to the political and cultural context. High levels of alcohol consumption can exaggerate supporter feelings and influence aggression, but this is neither the single nor the most important cause of hooliganism, given that many heavily intoxicated fans instead behave gregariously. In northern Europe fan violence has acquired an increasingly subcultural dimension. At major tournaments, self-identifying hooligans sometimes can spend weeks pursuing their distinctive peers among opposing supporters to engage in violence; the most successful combatants earn status within the subcultural network of hooligan groups. Research in Britain suggests these groups do not hail from society’s poorest members but usually from more-affluent working-class and lower middle-class backgrounds, depending upon regional characteristics. In southern Europe, notably in Italy, spectator violence can also reflect deep-seated cultural rivalries and tensions, especially between neighbouring cities or across the divide between north and south. In Latin America fan violence has been understood in relation to the modern politics of dictatorship and repressive state methods of social control. Moreover, the upsurge in violence in Argentina beginning in the late 1990s has been explained according to the severe decline of the national economy and the political system.

In some circumstances, football hooliganism has forced politicians and the judiciary to intercede directly. In England the Conservative government of the 1980s targeted football hooligans with legislation, and the subsequent Labour administration unveiled further measures to control spectator behaviour inside stadiums. In Argentina, football matches were briefly suspended by the courts in 1999 in a bid to halt the violence. Football authorities have also recognized fan violence as a major impediment to the game’s economic and social health. In England attempts at reducing hooliganism have included all-seated stadiums and the creation of family-only stands. These measures have helped attract new, wealthier spectators, but critics have argued that the new policies have also diminished the colour and atmosphere at football grounds. More liberal anti-hooligan strategies encourage dialogue with supporters: the “fan projects” run by clubs and local authorities in Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden are the strongest illustrations of this approach.

Still, the major threats to spectator safety tend to involve not fighting among supporters but rather a mixture of factors such as disorderly crowd responses to play in the match, unsafe facilities, and poor crowd-control techniques. In the developing world, crowd stampedes have caused many disasters, such as the 126 deaths in Ghana in 2001. Police attempts to quell disorderly crowds can backfire and exacerbate the dangers, as was the case in Peru in 1964 when 318 died and in Zimbabwe in 2000 when 13 died. Disastrous crowd management strategies and facilities that some have characterized as inhumane were at the root of the tragedy in Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield, England, in 1989, in which 96 were fatally injured when they were crushed inside the football ground.

It would be quite wrong, however, to portray the vast majority of football fans as inherently violent or xenophobic. Since the 1980s, organized supporter groups, along with football authorities and players, have waged both local and international campaigns against racism and (to a lesser extent) sexism within the game. Football supporters with the most positive, gregarious reputations—such as those following the Danish, Irish, and Brazilian national sides—tend to engage in self-policing within their own ranks, with few calls for outside assistance. As part of their Fair Play campaigns, international football bodies have introduced awards for the best-behaved supporters at major tournaments. In more challenging circumstances, English fan organizations such as the Football Supporters’ Federation have sought to improve the behaviour of their compatriots at matches overseas by planning meetings with local police officials and introducing “fan embassies” for visiting supporters. Across Europe, international fan networks have grown up to combat the racism that has also been reflected in some hooliganism. More generally, since the mid-1980s, the production of fanzines (fan magazines) across Britain and some other parts of Europe have served to promote the view that football fans are passionate, critical, humorous, and (for the great majority) not at all violent. Such fanzines have been supplemented by—and in many ways surpassed by—Internet fan sites in the 21st century.

Play of the game

The rules of football regarding equipment, field of play, conduct of participants, and settling of results are built around 17 laws. The International Football Association Board, consisting of delegates from FIFA and the four football associations from the United Kingdom, is empowered to amend the laws.

Equipment And Field Of Play

The object of football is to maneuver the ball into the opposing team’s goal, using any part of the body except the hands and arms. The side scoring more goals wins. The ball is round, covered with leather or some other suitable material, and inflated; it must be 27–27.5 inches (68–70 cm) in circumference and 14.5–16 ounces (410–450 grams) in weight. A game lasts 90 minutes and is divided into halves; the halftime interval lasts 15 minutes, during which the teams change ends. Additional time may be added by the referee to compensate for stoppages in play (for example, player injuries). If neither side wins, and if a victor must be established, “extra-time” is played, and then, if required, a series of penalty kicks may be taken.

The penalty area, a rectangular area in front of the goal, is 44 yards (40.2 metres) wide and extends 18 yards (16.5 metres) into the field. The goal is a frame, backed by a net, measuring 8 yards (7.3 metres) wide and 8 feet (2.4 metres) high. The playing field (pitch) should be 100–130 yards (90–120 metres) long and 50–100 yards (45–90 metres) wide; for international matches, it must be 110–120 yards long and 70–80 yards wide. Women, children, and mature players may play a shorter game on a smaller field. The game is controlled by a referee, who is also the timekeeper, and two assistants who patrol the touchlines, or sidelines, signaling when the ball goes out of play and when players are offside.

Players wear jerseys with numbers, shorts, and socks that designate the team for whom they are playing. Shoes and shin guards must be worn. The two teams must wear identifiably different uniforms, and goalkeepers must be distinguishable from all players and match officials.

Fouls

Free kicks are awarded for fouls or violations of rules; when a free kick is taken, all players of the offending side must be 10 yards (9 metres) from the ball. Free kicks may be either direct (from which a goal may be scored), for more serious fouls, or indirect (from which a goal cannot be scored), for lesser violations. Penalty kicks, introduced in 1891, are awarded for more serious fouls committed inside the area. The penalty kick is a direct free kick awarded to the attacking side and is taken from a spot 12 yards (11 metres) from goal, with all players other than the defending goalkeeper and the kicker outside the penalty area. Since 1970, players guilty of a serious foul are given a yellow caution card; a second caution earns a red card and ejection from the game. Players may also be sent off directly for particularly serious fouls, such as violent conduct.

Rules

There were few major alterations to football’s laws through the 20th century. Indeed, until the changes of the 1990s, the most significant amendment to the rules came in 1925, when the offside rule was rewritten. Previously, an attacking player (i.e., one in the opponent’s half of the playing field) was offside if, when the ball was “played” to him, fewer than three opposing players were between him and the goal. The rule change, which reduced the required number of intervening players to two, was effective in promoting more goals. In response, new defensive tactics and team formations emerged. Player substitutions were introduced in 1965; teams have been allowed to field three substitutes since 1995.

More recent rule changes have helped increase the tempo, attacking incidents, and amount of effective play in games. The pass-back rule now prohibits goalkeepers from handling the ball after it is kicked to them by a teammate. “Professional fouls,” which are deliberately committed to prevent opponents from scoring, are punished by red cards, as is tackling (taking the ball away from a player by kicking or stopping it with one’s feet) from behind. Players are cautioned for “diving” (feigning being fouled) to win free kicks or penalties. Time wasting has been addressed by forcing goalkeepers to clear the ball from hand within six seconds and by having injured players removed by stretcher from the pitch. Finally, the offside rule was adjusted to allow attackers who are level with the penultimate defender to be onside.

Interpretation of football’s rules is influenced heavily by cultural and tournament contexts. Lifting one’s feet over waist level to play the ball is less likely to be penalized as dangerous play in Britain than in southern Europe. The British game can be similarly lenient in punishing the tackle from behind, in contrast to the trend in recent World Cup matches. FIFA insists that “the referee’s decision is final,” and it is reluctant to break the flow of games to allow for video assessment on marginal decisions. However, the most significant future amendments or reinterpretations of football’s rules may deploy more efficient technology to assist match officials. Post-match video evidence is used now by football’s disciplinary committees, particularly to adjudicate violent play or to evaluate performances by match officials.

Strategy And Tactics

Use of the feet and (to a lesser extent) the legs to control and pass the ball is football’s most basic skill. Heading the ball is particularly prominent when receiving long aerial passes. Since the game’s origins, players have displayed their individual skills by going on “solo runs” or dribbling the ball past outwitted opponents. But football is essentially a team game based on passing between team members. The basic playing styles and skills of individual players reflect their respective playing positions. Goalkeepers require agility and height to reach and block the ball when opponents shoot at goal. Central defenders have to challenge the direct attacking play of opponents; called upon to win tackles and to head the ball away from danger such as when defending corner kicks, they are usually big and strong. Fullbacks are typically smaller but quicker, qualities required to match speedy wing-forwards. Midfield players (also called halfs or halfbacks) operate across the middle of the field and may have a range of qualities: powerful “ball-winners” need to be “good in the tackle” in terms of winning or protecting the ball and energetic runners; creative “playmakers” develop scoring chances through their talent at holding the ball and through accurate passing. Wingers tend to have good speed, some dribbling skills, and the ability to make crossing passes that travel across the front of goal and provide scoring opportunities for forwards. Forwards can be powerful in the air or small and penetrative with quick footwork; essentially, they should be adept at scoring goals from any angle.

Tactics reflect the importance of planning for matches. Tactics create a playing system that links a team’s formation to a particular style of play (such as attacking or counterattacking, slow or quick tempo, short or long passing, teamwork or individualistic play). Team formations do not count the goalkeeper and enumerate the deployment of players by position, listing defenders first, then midfielders, and finally attackers (for example, 4-4-2 or 2-3-5). The earliest teams played in attack-oriented formations (such as 1-1-8 or 1-2-7) with strong emphasis on individual dribbling skills. In the late 19th century, the Scots introduced the passing game, and Preston North End created the more cautious 2-3-5 system. Although the English were associated with a cruder kick-and-rush style, teamwork and deliberate passing were evidently the more farsighted aspects of an effective playing system as playing skills and tactical acumen increased.

Between the wars, Herbert Chapman, the astute manager of London’s Arsenal club, created the WM formation, featuring five defenders and five attackers: three backs and two halves in defensive roles, and two inside forwards assisting the three attacking forwards. Chapman’s system withdrew the midfield centre-half into defense in response to the 1925 offside rule change and often involved effective counterattacking, which exploited the creative genius of withdrawn forward Alex James as well as Cliff Bastin’s goal-scoring prowess. Some teams outside Britain also withdrew their centre-half, but others (such as Italy at the 1934 World Cup, and many South American sides) retained the original 2-3-5 formation. By the outbreak of World War II, many clubs, countries, and regions had developed distinctive playing styles—such as the powerful combative play of the English, the technical short-passing skills of the Danubian School, and the criollo artistry and dribbling of Argentinians.

After the war, numerous tactical variations arose. Hungary introduced the deep-lying centre-forward to confuse opposing defenders, who could not decide whether to mark the player in midfield or let him roam freely behind the forwards. The complex Swiss verrou system, perfected by Karl Rappan, saw players switch positions and duties depending on the game’s pattern. It was the first system to play four players in defense and to use one of them as a “security bolt” behind the other three. Counterattacking football was adopted by top Italian clubs, notably Internazionale of Milan. Subsequently, the catenaccio system developed by Helenio Herrera at Internazionale copied the verrou system, playing a libero (free man) in defense. The system was highly effective but made for highly tactical football centred on defense that was often tedious to watch.

Several factors contributed to the generation of more defensive, negative playing styles and team formations. With improved fitness training, players showed more speed and stamina, reducing the time and space for opponents to operate. The rules of football competitions (such as European club tournaments) often have encouraged visiting teams to play for draws, while teams playing at home are very wary of conceding goals. Local and national pressures not to lose matches have been intense, and many coaches discourage players from taking risks.

As football’s playing systems became more rationalized, players were no longer expected to stay in set positions but to be more adaptable. The major victim was the wing-forward, the creator of attacking openings, whose defensive limitations were often exposed. Internationally, Brazil became the greatest symbol of individualistic, flowing football. Brazil borrowed the 4-2-4 formation founded in Uruguay to win the 1958 World Cup; the tournament was widely televised, thus helping Brazil’s highly skilled players capture the world’s imagination. For the 1962 tournament in Chile, Brazil triumphed again, withdrawing one winger into midfield to create 4-3-3. England’s “Wingless Wonders” won the 1966 tournament with a more cautious variant of 4-3-3 that was really 4-4-2, employing no real wingers and a set of players more suited to work than creative passing or dribbling skills.

In the early 1970s, the Dutch “total football” system employed players with all-around skills to perform both defensive and attacking duties, but with more aesthetically pleasing consequences. Players such as Johan Cruyff and Johan Neeskens provided the perfect outlets for this highly fluent and intelligent playing system. Holland’s leading club—Ajax of Amsterdam—helped direct total football into a 3-4-3 system; Ajax’s long-term success was also built upon one of the world’s leading scouting and coaching systems, creating a veritable conveyor belt of educated, versatile players. However, hustling playing styles built around the now classic 4-4-2 formation have been especially prominent in Europe, notably as a result of the successes of English clubs in European competition from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s. The great Milan team of the late 1980s recruited the talented Dutch triumvirate of Ruud Gullit, Frank Rijkaard, and Marco van Basten, but their national and European success was founded too upon a “pressing” system in which opponents were challenged relentlessly for every loose ball.

The move towards efficient playing systems such as 4-4-2 saw changes in defensive tactics. Zonal defending, based on controlling specific spaces, became more prominent. Conversely, the classic catenaccio system had enabled greater man-to-man marking of forwards by defenders, with the libero providing backup when required. Subsequently, some European clubs introduced 3-5-2 formations using wingbacks (a hybrid of fullback and attacking winger) on either side of the midfield. Players such as Roberto Carlos of Real Madrid and Brazil are outstanding exponents of this new role, but for most wingbacks their attacking potential is often lost in midfield congestion and compromised by their lack of dribbling skills.

After 1990, as media coverage of football increased in Europe and South America and as the game enjoyed a rise in popularity, playing systems underwent closer analysis. They are now often presented in strings of four: 1-3-4-2 features a libero, three defenders, four midfielders and two forwards; 4-4-1-1 calls for four defenders, four midfielders, and a split strike force with one forward playing behind the other. The different roles and playing spaces of midfield players have become more obvious: for example, the four-player midfield diamond shape has one player in an attacking role, two playing across the centre, and one playing a holding role in front of the defenders.

Differences in playing systems between Latin American and European teams have declined markedly. During the 1960s and ’70s, Brazilian and Argentinian teams went through “modernizing” phases in which the European values of efficiency, physical strength, and professionalism were promoted in place of more traditional local styles that emphasized greater individualism and display of technical skills. South American national teams are now very likely to be composed entirely of players who perform for European clubs and to play familiar 3-5-2 or 4-4-2 systems.

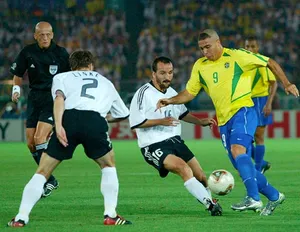

For all these tactical developments, football’s finest players and greatest icons remain the brilliant individualists: the gifted midfield playmakers, the dazzling wingers, or the second forwards linking the midfield to the principal attacker. Some leading postwar exponents have included Pelé, Rivaldo, and Ronaldo (Brazil), Diego Maradona and Lionel Messi (Argentina), Roberto Baggio and Francesco Totti (Italy), Michel Platini and Zinedine Zidane (France), George Best (Northern Ireland), Stanley Matthews and Paul Gascoigne (England), Ryan Giggs (Wales), Luis Figo, Eusébio, and Cristiano Ronaldo (Portugal), and Jim Baxter and Derek Johnstone (Scotland).

FIFA Men’s World Cup Winners

Winners of the FIFA men’s World Cup are provided in the table

| year | result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | Uruguay | 4 | Argentina | 2 |

| 1934 | Italy* | 2 | Czechoslovakia | 1 |

| 1938 | Italy | 4 | Hungary | 2 |

| 1950 | Uruguay | 2 | Brazil | 1 |

| 1954 | West Germany | 3 | Hungary | 2 |

| 1958 | Brazil | 5 | Sweden | 2 |

| 1962 | Brazil | 3 | Czechoslovakia | 1 |

| 1966 | England* | 4 | West Germany | 2 |

| 1970 | Brazil | 4 | Italy | 1 |

| 1974 | West Germany | 2 | Netherlands | 1 |

| 1978 | Argentina* | 3 | Netherlands | 1 |

| 1982 | Italy | 3 | West Germany | 1 |

| 1986 | Argentina | 3 | West Germany | 2 |

| 1990 | West Germany | 1 | Argentina | 0 |

| 1994 | Brazil** | 0 | Italy | 0 |

| 1998 | France | 3 | Brazil | 0 |

| 2002 | Brazil | 2 | Germany | 0 |

| 2006 | Italy** | 1 | France | 1 |

| 2010 | Spain* | 1 | Netherlands | 0 |

| 2014 | Germany* | 1 | Argentina | 0 |

| 2018 | France | 4 | Croatia | 2 |

| 2022 | Argentina** | 3 | France | 3 |

| *Won after extra time (AET). | ||||

| **Won on penalty kicks. | ||||

FIFA women’s World Cup winners

Winners of the FIFA women’s World Cup are provided in the table.

| year | result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | United States | 2 | Norway | 1 |

| 1995 | Norway | 2 | Germany | 0 |

| 1999 | United States* | 0 | China | 0 |

| 2003 | Germany | 2 | Sweden | 1 |

| 2007 | Germany | 2 | Brazil | 0 |

| 2011 | Japan* | 2 | United States | 2 |

| 2015 | United States | 5 | Japan | 2 |

| 2019 | United States | 2 | Netherlands | 0 |

| *Won on penalty kicks. | ||||

UEFA Champions League Winners

Winners of the UEFA Champions League are provided in the table.

| season | winner (country) | runner-up (country) | score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1955–56 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Stade de Reims (France) | 4–3 |

| 1956–57 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Fiorentina (Italy) | 2–0 |

| 1957–58 | Real Madrid (Spain) | AC Milan (Italy) | 3–2 (OT) |

| 1958–59 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Stade de Reims (France) | 2–0 |

| 1959–60 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Eintracht Frankfurt (W.Ger.) | 7–3 |

| 1960–61 | Benfica (Port.) | FC Barcelona (Spain) | 3–2 |

| 1961–62 | Benfica (Port.) | Real Madrid (Spain) | 5–3 |

| 1962–63 | AC Milan (Italy) | Benfica (Port.) | 2–1 |

| 1963–64 | Inter Milan (Italy) | Real Madrid (Spain) | 3–1 |

| 1964–65 | Inter Milan (Italy) | Benfica (Port.) | 1–0 |

| 1965–66 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Partizan Belgrade (Yugos.) | 2–1 |

| 1966–67 | Celtic (Scot.) | Inter Milan (Italy) | 2–1 |

| 1967–68 | Manchester United (Eng.) | Benfica (Port.) | 4–1 (OT) |

| 1968–69 | AC Milan (Italy) | Ajax (Neth.) | 4–1 |

| 1969–70 | Feyenoord (Neth.) | Celtic (Scot.) | 2–1 (OT) |

| 1970–71 | Ajax (Neth.) | Panathinaikos (Greece) | 2–0 |

| 1971–72 | Ajax (Neth.) | Inter Milan (Italy) | 2–0 |

| 1972–73 | Ajax (Neth.) | Juventus (Italy) | 1–0 |

| 1973–74 | Bayern Munich (W.Ger.) | Atlético Madrid (Spain) | 4–0** |

| 1974–75 | Bayern Munich (W.Ger.) | Leeds United (Eng.) | 2–0 |

| 1975–76 | Bayern Munich (W.Ger.) | AS Saint-Étienne (France) | 1–0 |

| 1976–77 | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | Borussia Mönchengladbach (W.Ger.) | 3–1 |

| 1977–78 | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | Club Brugge (Belg.) | 1–0 |

| 1978–79 | Nottingham Forest (Eng.) | Malmö FF (Swed.) | 1–0 |

| 1979–80 | Nottingham Forest (Eng.) | Hamburg SV (W.Ger.) | 1–0 |

| 1980–81 | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | Real Madrid (Spain) | 1–0 |

| 1981–82 | Aston Villa (Eng.) | Bayern Munich (W.Ger.) | 1–0 |

| 1982–83 | Hamburg SV (W.Ger.) | Juventus (Italy) | 1–0 |

| 1983–84 | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | AS Roma (Italy) | 1–1*** |

| 1984–85 | Juventus (Italy) | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | 1–0 |

| 1985–86 | Steaua Bucharest (Rom.) | FC Barcelona (Spain) | 0–0*** |

| 1986–87 | FC Porto (Port.) | Bayern Munich (W.Ger.) | 2–1 |

| 1987–88 | PSV Eindhoven (Neth.) | Benfica (Port.) | 0–0*** |

| 1988–89 | AC Milan (Italy) | Steaua Bucharest (Rom.) | 4–0 |

| 1989–90 | AC Milan (Italy) | Benfica (Port.) | 1–0 |

| 1990–91 | Red Star Belgrade (Yugos.) | Olympique de Marseille (France) | 0–0*** |

| 1991–92 | FC Barcelona (Spain) | Sampdoria (Italy) | 1–0 (OT) |

| 1992–93 | Olympique de Marseille (France) | AC Milan (Italy) | 1–0 |

| 1993–94 | AC Milan (Italy) | FC Barcelona (Spain) | 4–0 |

| 1994–95 | Ajax (Neth.) | AC Milan (Italy) | 1–0 |

| 1995–96 | Juventus (Italy) | Ajax (Neth.) | 1–1*** |

| 1996–97 | Borussia Dortmund (Ger.) | Juventus (Italy) | 3–1 |

| 1997–98 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Juventus (Italy) | 1–0 |

| 1998–99 | Manchester United (Eng.) | Bayern Munich (Ger.) | 2–1 |

| 1999–2000 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Valencia CF (Spain) | 3–0 |

| 2000–01 | Bayern Munich (Ger.) | Valencia CF (Spain) | 1–1*** |

| 2001–02 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Bayer Leverkusen (Ger.) | 2–1 |

| 2002–03 | AC Milan (Italy) | Juventus (Italy) | 0–0*** |

| 2003–04 | FC Porto (Port.) | AS Monaco (France) | 3–0 |

| 2004–05 | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | AC Milan (Italy) | 3–3*** |

| 2005–06 | FC Barcelona (Spain) | Arsenal (Eng.) | 2–1 |

| 2006–07 | AC Milan (Italy) | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | 2–1 |

| 2007–08 | Manchester United (Eng.) | Chelsea FC (Eng.) | 1–1*** |

| 2008–09 | FC Barcelona (Spain) | Manchester United (Eng.) | 2–0 |

| 2009–10 | Inter Milan (Italy) | Bayern Munich (Ger.) | 2–0 |

| 2010–11 | FC Barcelona (Spain) | Manchester United (Eng.) | 3–1 |

| 2011–12 | Chelsea FC (Eng.) | Bayern Munich (Ger.) | 1–1*** |

| 2012–13 | Bayern Munich (Ger.) | Borussia Dortmund (Ger.) | 2–1 |

| 2013–14 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Atlético Madrid (Spain) | 4–1 (OT) |

| 2014–15 | FC Barcelona (Spain) | Juventus (Italy) | 3–1 |

| 2015–16 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Atlético Madrid (Spain) | 1–1*** |

| 2016–17 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Juventus (Italy) | 4–1 |

| 2017–18 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | 3–1 |

| 2018–19 | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | Tottenham Hotspur (Eng.) | 2–0 |

| 2019–20 | Bayern Munich (Ger.) | Paris Saint-Germain (France) | 1–0 |

| *Known as the European Cup from 1955–56 to 1991–92. | |||

| **Final replayed after first match ended in a 1–1 draw. | |||

| ***Won in a penalty kick shoot-out. | |||

UEFA Europa League Winners

Winners of the UEFA Europa League are provided in the table.

| season | winner (country) | runner-up (country) | scores |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971–72 | Tottenham Hotspur (Eng.) | Wolverhampton Wanderers (Eng.) | 2–1, 1–1 |

| 1972–73 | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | Borussia Mönchengladbach (W.Ger.) | 3–0, 0–2 |

| 1973–74 | Feyenoord (Neth.) | Tottenham Hotspur (Eng.) | 2–2, 2–0 |

| 1974–75 | Borussia Mönchengladbach (W.Ger.) | FC Twente (Neth.) | 0–0, 5–1 |

| 1975–76 | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | Club Brugge (Belg.) | 3–2, 1–1 |

| 1976–77 | Juventus (Italy) | Athletic Club Bilbao (Spain) | 1–0, 1–2 |

| 1977–78 | PSV Eindhoven (Neth.) | SC Bastia (France) | 0–0, 3–0 |

| 1978–79 | Borussia Mönchengladbach (W.Ger.) | Red Star Belgrade (Yugos.) | 1–1, 1–0 |

| 1979–80 | Eintracht Frankfurt (W.Ger.) | Borussia Mönchengladbach (W.Ger.) | 2–3, 1–0 |

| 1980–81 | Ipswich Town (Eng.) | AZ Alkmaar (Neth.) | 3–0, 2–4 |

| 1981–82 | IFK Göteborg (Swed.) | Hamburg SV (W.Ger.) | 1–0, 3–0 |

| 1982–83 | RSC Anderlecht (Belg.) | Benfica (Port.) | 1–0, 1–1 |

| 1983–84 | Tottenham Hotspur (Eng.) | RSC Anderlecht (Belg.) | 1–1, 1–1 (4–3**) |

| 1984–85 | Real Madrid (Spain) | Videoton (Hung.) | 3–0, 0–1 |

| 1985–86 | Real Madrid (Spain) | FC Cologne (W.Ger.) | 5–1, 0–2 |

| 1986–87 | IFK Göteborg (Swed.) | Dundee United (Scot.) | 1–0, 1–1 |

| 1987–88 | Bayer Leverkusen (W.Ger.) | RCD Espanyol (Spain) | 0–3, 3–0 (3–2**) |

| 1988–89 | SSC Napoli (Italy) | VfB Stuttgart (W.Ger.) | 2–1, 3–3 |

| 1989–90 | Juventus (Italy) | Fiorentina (Italy) | 3–1, 0–0 |

| 1990–91 | Inter Milan (Italy) | AS Roma (Italy) | 2–0, 0–1 |

| 1991–92 | Ajax (Neth.) | Torino Calcio (Italy) | 2–2, 0–0 |

| 1992–93 | Juventus (Italy) | Borussia Dortmund (Ger.) | 3–1, 3–0 |

| 1993–94 | Inter Milan (Italy) | SV Austria Salzburg (Austria) | 1–0, 1–0 |

| 1994–95 | Parma AC (Italy) | Juventus (Italy) | 1–0, 1–1 |

| 1995–96 | Bayern Munich (Ger.) | FC Girondins de Bordeaux (France) | 2–0, 3–1 |

| 1996–97 | FC Schalke 04 (Ger.) | Inter Milan (Italy) | 1–0, 0–1 (4–1**) |

| 1997–98 | Inter Milan (Italy) | SS Lazio (Italy) | 3–0 |

| 1998–99 | Parma AC (Italy) | Olympique de Marseille (France) | 3–0 |

| 1999–2000 | Galatasaray SK (Tur.) | Arsenal (Eng.) | 0–0 (4–1**) |

| 2000–01 | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | Deportivo Alavés (Spain) | 5–4 |

| 2001–02 | Feyenoord (Neth.) | Borussia Dortmund (Ger.) | 3–2 |

| 2002–03 | FC Porto (Port.) | Celtic (Scot.) | 3–2 |

| 2003–04 | Valencia CF (Spain) | Olympique de Marseille (France) | 2–0 |

| 2004–05 | CSKA Moscow (Russia) | Sporting Clube de Portugal (Port.) | 3–1 |

| 2005–06 | Sevilla FC (Spain) | Middlesbrough FC (Eng.) | 4–0 |

| 2006–07 | Sevilla FC (Spain) | RCD Espanyol (Spain) | 2–2 (3–1**) |

| 2007–08 | FC Zenit St. Petersburg (Russia) | Rangers (Scot.) | 2–0 |

| 2008–09 | Shakhtar Donetsk (Ukr.) | Werder Bremen (Ger.) | 2–1 |

| 2009–10 | Atlético de Madrid (Spain) | Fulham FC (Eng.) | 2–1 |

| 2010–11 | FC Porto (Port.) | SC Braga (Port.) | 1–0 |

| 2011–12 | Atlético de Madrid (Spain) | Athletic Club Bilbao (Spain) | 3–0 |

| 2012–13 | Chelsea FC (Eng.) | Benfica (Port.) | 2–1 |

| 2013–14 | Sevilla FC (Spain) | Benfica (Port.) | 0–0 (4–2**) |

| 2014–15 | Sevilla FC (Spain) | Dnipro (Ukr.) | 3–2 |

| 2015–16 | Sevilla FC (Spain) | Liverpool FC (Eng.) | 3–1 |

| 2016–17 | Manchester United (Eng.) | Ajax (Neth.) | 2–0 |

| 2017–18 | Atlético de Madrid (Spain) | Olympique de Marseille (France) | 3–0 |

| 2018–19 | Chelsea FC (Eng.) | Arsenal (Eng.) | 4–1 |

| *UEFA Cup until 2009–10. | |||

| **Won in a penalty kick shoot-out. | |||

Major League Soccer (MLS) Cup Winners

Winners of the MLS Cup are provided in the table.

| year | winner | runner-up | score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | DC United | Los Angeles Galaxy | 3–2 (OT) |

| 1997 | DC United | Colorado Rapids | 2–1 |

| 1998 | Chicago Fire | DC United | 2–0 |

| 1999 | DC United | Los Angeles Galaxy | 2–0 |

| 2000 | Kansas City Wizards | Chicago Fire | 1–0 |

| 2001 | San Jose Earthquakes | Los Angeles Galaxy | 2–1 (OT) |

| 2002 | Los Angeles Galaxy | New England Revolution | 1–0 |

| 2003 | San Jose Earthquakes | Chicago Fire | 4–2 |

| 2004 | DC United | Kansas City Wizards | 3–2 |

| 2005 | Los Angeles Galaxy | New England Revolution | 1–0 (OT) |

| 2006 | Houston Dynamo | New England Revolution | 1–1* |

| 2007 | Houston Dynamo | New England Revolution | 2–1 |

| 2008 | Columbus Crew | New York Red Bulls | 3–1 |

| 2009 | Real Salt Lake | Los Angeles Galaxy | 1–1* |

| 2010 | Colorado Rapids | FC Dallas | 2–1 (OT) |

| 2011 | Los Angeles Galaxy | Houston Dynamo | 1–0 |

| 2012 | Los Angeles Galaxy | Houston Dynamo | 3–1 |

| 2013 | Sporting Kansas City | Real Salt Lake | 1–1* |

| 2014 | Los Angeles Galaxy | New England Revolution | 2–1 |

| 2015 | Portland Timbers | Columbus Crew | 2–1 |

| 2016 | Seattle Sounders | Toronto FC | 0–0* |

| 2017 | Toronto FC | Seattle Sounders | 2–0 |

| 2018 | Atlanta United | Portland Timbers | 2–0 |

| 2019 | Seattle Sounders | Toronto FC | 3–1 |

| 2020 | Columbus Crew | Seattle Sounders | 3–0 |

| 2021 | New York City FC | Portland Timbers | 1–1* |

| 2022 | Los Angeles FC | Philadelphia Union | 3–3* |

| *Won on penalty kicks. | |||